A Story by Karin Joshua Paritzky

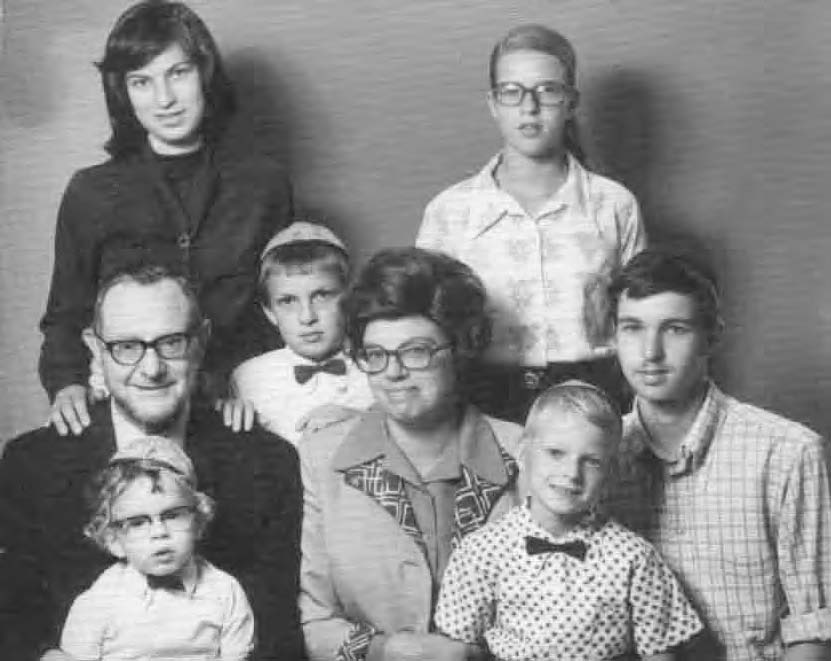

Back row: Shifra Aron Emanuel, Shaya Paritzky and Chana Aron Ulman

Introduction and Editing by Henry Joshua

Introduction

In the beginning of 1984 my sister, Karin Joshua, enrolled in a creative writing course. An assignment for the course was to write a story. “The Last Gift” was the result. A few of those that read it suggested that it should be made available to a wider audience. In September 2003 I asked Karin whether she agreed to have it published and her answer was affirmative. A month later she suffered a massive stroke and she has been in a coma ever since. At this point I just want to make some copies for family and friends in English and I hope that I could have it translated also into Hebrew for her Hebrew-speaking family and friends.

(circa 1905)

The story is based on the history of the Joshua family between approximately 1880 and 1945. The Joshua family lived in Hamburg the “bustling city at the Northern Sea” for several generations. Lodevic and Yohanna refer to my paternal grandparents Ludwig and Johanna Joshua. Ludwig was born on July 9, 1860 in Hamburg while Johanna was born on September 12, 1864 in Copenhagen, Denmark. They were married on December 18, 1892. They had two children, Lissie (Belissa in the story) born on May 13, 1894 and Max (my father, Maxim in the story), born on May 30, 1895. My father attended the Talmud Tora Realschule in Hamburg. The school was founded in 1805.He graduated the ten year curriculum in 1911. In the spring of that year he passed a rigorous State examination. The oral part of the examination took place on March 1 and 2. Similarly Max’s father, Ludwig, had attended the same school and passed the written and oral State examination in the subjects of German, mathematics, English and French (1, 2).

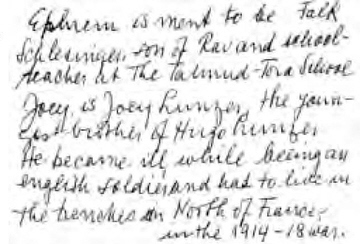

“Ephrem is meant to be Falk Schlesinger, son of Rav and schoolteacher at the Talmud-Tora School. Joey is Joey Lunzer, the youngest brother of Hugo Lunzer. He became ill while being an English soldier and had to live in the trenches in North of France in the 1914-18 war.”

Falk Schlesinger was born in 1895 in Hamburg, the same year as my father. Falk’s father was Eliezer Lipman Schlesinger who taught at the Talmud Tora School from 1889 to 1926 (2). Falk had two brothers and a sister. He studied medicine and became Director and Chief Physician of Shaarei Zedek Hospital in Jerusalem from 1947 to his death in 1968. Another son of Eliezer Lipman Schlesinger was Harav Yechiel Michel Schlesinger who was Dayan in Frankfurt. He moved to Jerusalem in 1939 where he cofounded Yeshivat Kol Torah.

Lissie Joshua married Friedrich Mainz, a banker, in 1918. He was born on April 7, 1890 in Hamburg. They were saved from the Holocaust by taking a freighter ship from Holland. They disembarked in Lorenzo Marques (now Maputo), the capital of Mozambique where they stayed for the duration of World War II. Subsequently they moved to Johannesburg in South Africa.

The South American passport which gave us “preferred status” was sent to us by Chaim Yisroel Eiss. Mr. Eiss lived in Zurich where he worked assiduously to save Jews who were about to be sent to their death. Recent articles describe his tremendous efforts (4,5,6,7).

The “young Dutch Rabbi” was Rabbi Aron Schuster. He was born August 8, 1907 in Amsterdam, he studied classic languages at Amsterdam University and also studied at the “Nederlands-Israelietisch Seminarium.” He received Rabbinical ordination in 1941. Except for a daughter who was hidden, the Schuster family consisting of Rabbi Schuster, his wife, son and stepson were taken into custody on May 26, 1943, transported to Westerbork and on February 11, 1944 taken to Bergen-Belsen. They were freed on a train near Trobitz by the Russian army. Of the fifteen Dutch Rabbis that were deported (eleven were in Bergen-Belsen) only Rabbi Schuster survived. He returned to Holland after the war and played an important role in the rebuilding of Amsterdam and Dutch Jewry. In 1972 he retired to Jerusalem where he died on September 7, 1994 (8,9,10).

Elisabeth Eisenmann Joshua

References for Introduction

- Information from Ursula Randt in an e-mail dated 7/5/2005.

- Ursula Randt, “Die Talmud Tora Schule in Hamburg” which was published in 2005 on the two hundredth anniversary of its founding.

- Information from R. Halenbrenner, Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities, Zurich, e-mail, 3/9/2006.

- Chaim Shalem, ““Remember, There are not Many Eisses Now In The Swiss Market”: Assistance and Rescue Endeavors of Chaim Yisrael Eiss in Switzerland.” published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2005 in Yad Vashem Studies 33.

- Shoshanna Goldfinger, a Great-Granddaughter, “Reb Chaim Yisroel Eiss, the Man at the center of Orthodoxy’s World War II Rescue Activities”, Dei’ah Vedibur, August 9, 2004.

- S. Goldfinger, “Chareidim Led the Hatzoloh Network in Europe”, Dei’ah Vedibur, February 1, 2006.

- S. Goldfinger, “Reb Chaim Yisroel Eiss, the Man at the center of Orthodoxy’s World War II Rescue Activities http://planet.nana.co.il/eiss/english.htm

- Willy Lindwer, “Kamp van Hoop en Wanhoop, Getuigen van Westerbork, 1939-1945″, pages181-187.

- Thomas Rahe, “Rabbiner im Konzentrationslager Bergen-Belsen”, in Menora, Jahrbuch fuer deutsch-juedische Geschichte, 1998, pages 121-151.

- Mrs. Kresniker, daughter of Rabbi Schuster, in a telephone conversation in 2005 gave me many interesting details of her father’s life. She lives in Bait Vegan, in Jerusalem.

Karin’s professional career included secretarial duties at Philipp Brothers Inc., the commodity trading firm, between 1949 and 1953 in New York City, secretary to Dr. Falk Schlesinger at the Sharei Zedek Hospital in Jerusalem between 1954 and 1968. Subsequently she was secretary for approximately ten years to Rabbi Menachem Porush, Member of the Knesset and Chairman of Agudas Israel in Israel.

Karin translated a number of books from German to English including “ From the Wisdom of Mishle” by Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, “The Nineteen Letters” by Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, “The Rav” by Naftali Hertz Ehrmann, and “The Hirsch Haggadah” by Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch.

Karin’s Family Tree

Max (Moshe) Joshua 30.5.1895-16.1.1945 married on 8.2.1929

Elisabeth (Elisheva) Eisenmann 27.10.1902-23.8.1998

Karin (Tova Gitel) 11.3.1930 married on 13.5.1955

Meir Nathan (Manfred) Aron 24.9.1924-24.7.1961

Moshe Menachem Aron 22.7 1956 married on 8.8.1979

Aviva Sharon (Adler) 27.6.1957

Nechama 22.3.1982 married on 8.7.2003 Aron Flam

Chaim Meir Nosan 12.9.2004, 26 Elul 5764

Nathan 24.9.1983 married on 3.3.2005 Penina Kehane, 22 Adar 1, 5765

Eliahu Eliezer 2.11.1984

Meir 15.12.1985

Yehoshua 5.3.1988

Chaim Dovid 14.10.1989

Chizkiyahu 7.4.1991

Elchanan 29.8.1992

Uri Shraga 26.3.1994

Nethanel 17.12.2001

Shifra 25.7.57 married on 6.12.1976

Michael Yechiel Emanuel 15.1.1952

Dina 1.12.1977 married on 24.6.1997 Eliezer Turk

Mordechai Yechezkel 1.6.1998

Elisheva 17.11.1999

Yisrael Meir 10.1.2002

Benjamin 26.12.2003

Meir 5.6.1979 married on 25.2.2001 Miriam Leah Hofner 10.3.1981

Naftali 17.6.2002

Ruchama 1.7.2003

Nesanel 23.10.2003, 8 Cheshvan 5765

Yaakov 4.5.1981 married on 21.10.2003 Rachel Leah Erlanger 16.1.1983

Eliezer 4.10.2004, 19 Tishrei, 5765, Shabbos Lech-Lecho

Rachel 6.1.1983 married on 30.10.2004, 17 Kislev 5765

Aron Katz

Shemuel 9.7.1984

Yehuda 18.2.1986

Yael 23.4.1989

Channa 3.10.1990

Yitzchak 23.7.1992

Shlomo 23.3.1994

Ruth 19.2.1996

Channa 9.2.1960 married on 23.10.1979

Yisroel Ullman 13.10.1957

Naomi 25.6.1981 married on 23.8.2000 Bezalel Yakov Fuchs 16.8.1977

Yehuda Yitzchak 27.6.2002

Eliyahu 7.11.2003

Nathan 2.8.1983 married on 18.8.2003Ayala Murdechovitz 14.12.1983

Eliahu 6.6.1986

Moshe 13.3.1988

Shemuel 28.6.1989

Yehudith 30.4.1991

Shlomith 19.1.1993

Bracha 17.1.1995

Nechama 17.7.1996

David 5.3.2002

Shlomo 4.3.2004, 11 Adar 5764

Karin married on 7.2.1964

Chaim Paritzky 27.6.1922

Yeshaya 18.9.1965 married on 21.2.1988

Rivka (Viler) 2.12.1968

Naome Zippe 11.12.1988

Shoshana 19.6.1994

Chava 15.2.1996

Ruth 14.5.1998

Yehuda 12.6.2000

Mordechai 1.3.2003

Elisheva 28.7.2005, 21 Tammuz 5765

Avraham Jacob 19.12.1968 married on 10.2.1991 02-6422732

Esther (Hofner) 17.3.1971

Aron 22.10.1992

Shemuel 25.4.1996

Eliahu 2.10.1996

Nechama 19.7.1998

Benjamin 19.11.1999

Naftoli 18.9.2001

Yochanan 13.12.2003

Meir Yecheskel 29.4.1973

THE LAST GIFT

I

The year was 1926 and Max was on his way to Switzerland in the hope that the mountain air would rid him of his tuberculosis. From his city, Hamburg, to Davos in Switzerland, the trip was long and wearisome. So far he was alone in the train compartment and no one but an occasional porter or comptroller interrupted his daydreaming. So Max could talk to his children, undisturbed, to the accompaniment of the clattering train wheels and against the backdrop of kaleidoscoping landscapes framed by the windows. He was telling his children the story of his family.

Of course he did not have any children at all. He was still unwed. But perhaps, by preparing the story, he willed it that he should one day have a family and children of his own. Perhaps a daughter like his sister Belissa and a son like his friend Ephrem, for it is said that one’s sons resemble their mother’s brother…

Dear Children,

Once upon a time, in a big and bustling port city at the Northern Sea, where many ships anchored and through which many sailors, traders and travelers passed, there lived a young man and his bride. The young man’s name was Lodevic and his wife was called Yohanna.

With the money Yohanna’s father had given them as a dowry, Lodevic purchased some cowhides from a merchant at the port and, after having these tanned, set up a trade in leather and hides. Soon his business prospered.

One day Yohanna said to her husband: “Lodevic, with G’d’s help we will have a child in a few months’ time.” Lodevic rejoiced in his heart and replied: “Yohanna, we will then need a bigger house. I saw a fine house for sale, on a wide street. Will you come with me and see if you like it?” It was indeed a fine and friendly house with a wide door, full-length windows and a gabled roof. Yohanna liked it very much and so they bought it and made it into a good home for themselves, for their yet unborn child, as well as for friends and guests and for sojourners from abroad who would tell many a stirring tale about foreign peoples and lands, strange tribes and exotic animals.

Now Lodevic and Yohanna’s ancestors had belonged to an ancient people. The leaders of this people were wise men to whom the story of the creation of the world had been transmitted from one generation to the next and who knew about the One G’d Who had created it. When Lodevic was still a boy, only a few of these wise men were left in his country. But Lodevic’s father had known one of them and had brought his son to him in order to be taught some of the ancient wisdom of the world. Lodevic had respected his teacher and had learned much from him about the Creator and His ways. Now he no longer studied the books of wisdom, but his respect abided and when he met his former teacher he doffed his hat and exchanged good wishes with him.

In time a girl was born to Lodevic and Yohanna, whom they called Belissa, and the year after, a boy, whom they named Maxim. Belissa had large gray eyes and a straight nose. When she was five years old, Yohanna tied her curly hair into a little bun and dressed her in a long dress with ruffles at the neck, just like herself.

Belissa loved her brother very much and Maxim loved her in return. Soon they could be seen together on their way to school, wearing straw hats in the summer and wool caps in winter. After school Belissa liked to stand at one of the windows facing the street and look at the horse-and-buggies, the ladies in their bobbing hats and the gentlemen in their greatcoats or military uniforms. Sometimes she invited her friends, little girls with flounced gowns and lacquered shoes. But Maxim made friends with Ephrem, the son of the wise man who had once taught his father and he would often ask permission to visit at the home of his friend. He would then join Ephrem’s family at the large round table with the tasseled tablecloth. Ephrem’s father would be studying in the ancient books, while the two boys prepared their homework.

When Maxim was fourteen years old, his father called him into his office and said:

“Max, you have graduated from school with distinction. Your mother and I are proud of you. You write a fine hand and excel in English and mathematics. From now on you shall help in the business.”

And so he did during the day. But at night he went to his friend’s house and together they would study the ancient texts. Sometimes he lifted his eyes from the book and let them linger on Ephrem’s sisters, seated around the table writing or embroidering, and the light from the round lamp fell on their braided hair. Sometimes he would join them at their family meals in celebration of one of their festivals and would lift his voice in their singing of praises to the Creator or in their memorial services intoning their plaints in mourning of their old destroyed temple.

One day a rumor was heard in the city. It was about a shooting, the murder of a royal prince in a neighboring country. The people said that this meant war, that it would reach them, too, and that their sons would have to fight in the war.

In that year Belissa had become seventeen years old and had grown to be very beautiful. Lodevic and Yohanna introduced her to the son of a friend of the family, a wealthy banker, Belissa and Frederic greatly pleased each other. Their wedding was arranged and Lodevic and Yohanna invited the wise man to consecrate the young couple’s marriage.

The dire predictions had come true. A bitter and bloody war had broken out between the country on the Northern Sea and the other countries. The sons of the ancient people very much loved the land on the Northern Sea though it was not where the cradle of their ancestors had stood centuries before. But they had lived there for many generations during many epochs and served it with deep loyalty. Their sons enlisted in the army and many of them died a hero’s death. Maxim was too young for service so he only helped his father manufacture sturdy kitbags and saddlegear for the soldiers.

In the evenings he continued to study with Ephrem, and now Ephrem’s father taught them the difficult passages.

After four years of fierce battles, the army of the country on the Northern Sea was defeated. Its people were sick at heart for they had lost everything and gained nothing. Indeed, countless parents were bereaved. From a prosperous country they had been reduced to a land of ruins and cripples, of orphans and widows and paupers. Lodevic, too, lost his livelihood since there was no longer any need for his leather goods. In fact, Lodevic and Yohanna became so poor, they had to give up their beautiful house for a very small one; Maxim’s room was in the basement. Many other people, too, were impoverished and they grew very bitter. And out of bitterness they wanted to blame someone. Some people whispered among themselves that they knew who was to blame. Soon others repeated the whisper and even said it out loud. They knew the cause of their defeat and their poverty, they knew who was responsible: it was the ancient people!

Max, too, was hungry and cold in his damp basement room and soon started coughing, a dangerous cough. He might, perhaps, recover from his illness, the doctor had said, but he would have to travel to the highest mountains. Belissa’s husband advanced the money for the fare.

On the night preceding his departure. Max went to Ephrem’s house to take leave of him and his family. Ephrem’s father laid his two hands on Max’s head in the age-old way of his people, and blessed him.

That night Max had a dream. In his dream he was a child playing in front of a house, their old house in the wide street. Looking up he saw his father standing behind the middle full-length window, nodding and smiling to him. When Max looked up next, his father was no longer there. In sudden panic, nameless fear having taken possession of him, he raced up the staircase to look for his father but couldn’t find him. He wanted to scream, “Father, father, where are you?” Panting, he climbed the last steep steps to the attic and there he found his father crouching in front of the shuttered casement windows, looking out to the street through the chinks. In his dream, Max sobbed and cried out: “Father, I thought you were dead.” But Lodevic calmly answered: “But no, you silly boy, I can observe you better from the attic window. It is just that you cannot see me!”

II

The train came to a halt. Already the sun had rolled down behind the mountains and dusk had swept across the countryside. The shadows of the Alps lengthened perceptibly. To Max they seemed like the threatening paws of a huge animal stealthily encroaching on him. Taking his luggage, he stepped out on the parapet where the local shuttle to the sanatorium would be meeting the express train on which he had just arrived. A young man of his own age, dressed in a long, fur-collared plaid coat and a visor cap, his complexion florid with the false brilliancy characteristic of their common illness, was the only other passenger waiting.

Whether it was the awareness of their common lot, or that of their both being Jewish, though from different countries, they sensed an instant affinity and, when the train rolled into the station, took their seats in the same compartment.

Affected by the change in altitude, Max dozed off. When, at last, they alighted in Davos, an employee from the sanatorium was waiting for them in the dimly lit, drafty station. The two young men followed him in silence. Even the sound of their footsteps was muffled by the snow.

As they entered the warm and well-lit lobby of the sanatorium, the clinking of cutlery and the hum of animated voices wafted through the dining-room doors.

“Would you like to join me at my table?” asked Joey before Max was shown upstairs to his room.

“Gladly,” answered Max.

“And that,” Max would later tell his children, “was how our friendship began.”

Side by side in their lounging chairs, through shielded eyes they would follow the flight of the black ravens silhouetted against the snowcovered fir trees and the distant mountaintops. Together they would take the prescribed daily walks, occasionally accompanied by some of the always high spirited young women, for as long as Joey was still able to do so. Sometimes they would join other patients in their revels — not always compatible with the doctors’ guidelines — in the “Kurhaus,” but this, too, as Joey’s condition worsened, became rarer.

When it came to birthdays or other landmarks in the lives of the members of his family, or those of the staff and other patients in the sanatorium, Max always thought of little considerations, whether it was a bouquet of pressed Edelweiss he had picked during a walk, or a humorous poem he had composed for the occasion.

Both he and Joey had brought some books of Jewish studies from home, and for an hour or two each day, they would explore the volumes together. And they talked. When letters arrived from their respective homes, they shared the news. Once a letter came from Ephrem announcing the happy tidings of his sister’s engagement and forthcoming marriage.

“How is it,” Joey once asked, his words interrupted by a paroxysm of coughing, “that the relationship of G’d to the Jewish people is so often compared to that of man and wife?”

Answering himself, he continued, “I wonder… I suppose that, if our sages were able to project this relationship to the highest conceivable realm, then…then their own marriage must have had this quality of sanctity…” “Did you ever consider marriage?”

“Certainly,” and Max thought of Ephrem’s sister and the children he had visualized, “did you?”

“Yes,” said Joey. “Max,” he hesitated, “if I don’t make it, will you go and see her? Her name is Elsa.” His friend bowed his head in silent assent.

Summer came and Max’s health improved, but Joey’s condition worsened and one day they quietly took him away. Of the sanatorium patients, only Max accompanied him to the small Jewish cemetery.

By October Max had improved sufficiently to leave the sanatorium with a strong probability never to have to return. On his way to the station he made a last visit to Joey’s grave and then took the train to the city in which Elsa lived. He had first taken the precaution of writing to ask her if she would meet him in the lobby of a well-known hotel. When he entered, he spotted her at once. She was sitting in the twilight — the lights hadn’t been switched on yet — her back was to the plate-glass window, and light from the street lamp outside made her short wispy hair stand out like a luminous frame to her thin, lively face, now in repose. A surge went through him, of joy and, unaccountably, of pity.

“And that, children.” Max told them later, “Is how I met your mother…”

Their marriage had been blessed with three children, the first-born a girl and then two boys. The year was 1943 and Max, Elsa, and their children were on a train being borne to a concentration camp, a camp, Max conjectured, where the Jewish population was brought together, “concentrated” so to speak, as the word implied. Their train was not one of cattle-wagons, such as those on which the other inmates of the transit camp were being transported week after week. They were traveling on a real passenger train. Thanks to Elsa’s initiative, Max’s family had obtained South American passports and had been assigned “preferred status” by the Gestapo.

For the first time in seven years. Max was able to relax. No longer did he need to plan escape, nor worry where money was to come from, nor to hide or sell possessions, to fill out forms for deferment of transport. No longer did Elsa have to forage for whatever provisions they needed, no longer did they have to live with the unrelenting fear of being “picked up,” as it was called. Now, inexorably, they had indeed been “picked up,” were caught and “put on transport.” They were on their way to the “concentration” camp, Bergen-Belsen, near Celle, on the Lueneburger Heath.

He looked at his family there in the train compartment, his oldest, so tall for her thirteen years and so very thin. Once, two years ago already, Elsa had taken her to the doctor for a checkup because of weakness. The doctor had prescribed one hundred grams of meat each day. When Elsa and the girl had come home, they had all roared with laughter at that preposterous, unattainable prescription. And even later, when someone looked about hungrily at the empty table, one of the children would say “a hundred grams of meat, please,” and they would burst out laughing. Then there were the two boys, eleven and eight, now quietly peering out of the window. And Elsa, so tired and worn. Well, perhaps they were being sent to greener pastures. After all, they had “preferred status.”

He would have liked to tell the children how all of this had come about, how the evil man they knew so well had magnified the malignant whispers into a virulent shout, how he had taken the shuffling feet of the unemployed and uneducated and shod them with stamping boots and how the stamping and shouting had grown into a deafening roar: “e-ra-di-cate and wipe-them-out, the ancient Jewish people,” as repetitious and mindless as the very train wheels stamping underneath them, and probably as methodical and relentless in reaching their goal, he thought. But this was not exactly the setting to tell stories to children, he thought wryly. Perhaps when all this was over.

And Elsa, his faithful companion. Once she had given their daughter, after a childish bout of petulance, a framed saying: “Thus be and remain, despite days of gloom, to make people happy, when you enter the room.”

Puerile, he knew. But the fact remained, Elsa had set the example, whatever the gloom, the constant fear and tension, the want and the harsh drudgery, the moving from one place to the other, uncomplaining, faith and hope springing from her innermost conviction, finding their expression in the observance of the daily commandments of the Jewish law as a matter of course. Not in an ostrich-like way, though, he thought. On the contrary, she, Elsa, had been more wide awake to the dangers and had assessed them more realistically than most.

But Max’s musings were interrupted. The train had stopped. They were in Bergen Belsen.

III

The girl was looking out from behind the barbed-wire fence separating the barracks compound from the central camp road. She was waiting for the work-commandos shuffling back to the camp enclosure in rows of five, rows of five. Today the procession was slightly different from other days. One of the prisoners apparently had collapsed at work and was now being borne by two of the other prisoners. He was hanging down lifelessly, like a straw puppet between them. In this way, he was being dragged along, in front of the many columns of prisoner-workers. From inside the fence the girl looked more closely. The man who had fainted was her father.

Blindly, unthinkingly, she ran. She ran, all alone, crossing the huge parade grounds, the empty Appell-field awaiting the commandos to return and stand at attention in rows of five, rows of five. Blindly, unthinkingly she raced to the entrance gate where two German soldiers stood poised to count the hundreds of prisoners about to enter. Stupid, unthinking. But the German merely screamed at her: “What are you doing here?” “It is my father,” the girl said calmly, as if addressing a human being. Then she joined the men just entering who were propping up her father and the foursome slowly walked over the field. It was the last time Max crossed the Appell-field. At least in that direction.

From now on. Max no longer was called to work outside of the barracks compound. He stayed “home”, on the lowest level of the three-tiered bunk. He shared his bunk with a young Dutch rabbi. He stayed “home” with the bugs, the vermin, the squalor and the hunger, his body bloated with starvation-oedema, getting up only for his daily prayers.

From the women’s barracks, Elsa came to visit him whenever possible. In addition to her work in the commando unit outside, she had taken another job in the camp, washing dirty underwear in exchange for a food ration. It was strange, Max thought, how people remained themselves, true to their characteristics regardless of changing circumstances. True ladies remained ladies in behavior and true gentlemen retained their basic nobility, regardless. Hunger did not make thieves of honest people, nor did adversity turn the staunch into whiners. Elsa had remained herself, too, he thought. Though her body was emaciated, her spirit had remained undaunted, courageous and purposeful. It was good to have her.

Max, too, hadn’t changed, basically. He was planning a surprise for his wife’s birthday. He had consulted with Joey with whom, lately, he was having long conversations. Joey had said that it should be a song. And so, for the next three weeks, the young Dutch rabbi, Max’s bed mate, could be seen walking between the barracks, under the eyes of the German guards on their watchtowers, teaching three children the song of King David, as it is written:

“I will lift up my eyes to the hills. From whence comes my help? My help comes from the Lord, Who made heaven and earth. He will not suffer thy foot to be moved: He Who keeps thee will not slumber. The Lord is thy keeper: the Lord is thy shade upon thy right hand. The sun shall not smite thee by day, nor the moon by night. The Lord shall preserve thee from all evil: He shall preserve thy soul. The Lord shall preserve thy going out and thy coming in from this time forth, and for evermore.” (Psalms 121)

And when the children sang this song to their mother, as a tribute from a husband to his wife and in honor of G’d, G’d heard the song and He was very surprised for only a very few songs of faith came up to the heavens in these terrible times He had decreed something so incomprehensibly upon His children. He peered through a tiny chink He had left in His pitch dark heavens and saw the birthday party alongside Max’s bunk. “For this,” He said to Max, who was already attuned to His voice,

“I shall elevate you to the light of my brightest heavens and to the music of my most sonorous harps. As for your wife and children, I will cause them to survive this Holocaust and they and their generations shall spread My song on earth for all times to come.”

Written in February 1984